Portraits: What you lookin' at?

an online exhibition

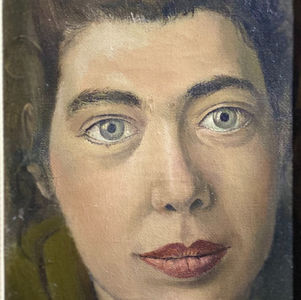

Portraiture, alongside figurative painting, is an early form of art going back at least to ancient Egypt, 5000 years ago. As a record, as propaganda, as advertisement – the portrait can be many things beyond the factual representation of a person. Used to show power, wealth, importance, beauty, virtue, status and other qualities, the portrait almost always depicted the sitter in a flattering light. However, with the decline of the patronage model (in which the artist was commissioned to work, rather than producing work which was then for sale) portraiture began to show the reality of people, rather than the version they wished to show.

The artist has always had the power to manipulate the image – creating the portrait they, and their sitter, wanted to share with the wider world. Until the nineteenth century this often entailed the sitter wearing fashionable clothing, or fantastical costume, elaborate props or allegorical settings. By the twentieth century artists were seeking new forms of expressing character, personality and appearance. It was no longer just about the visual portrait, but also the physiological, socio-economical and the moral portrait. With the advent and advancement of photography questions of voyeurism permeated into art, reframing questions about looking and being looked at which art had always grappled with.

This exhibition looks at known and unknown figures - portraits which depict named people, and those which feature figures as their subject. Some of the sitters stare out of the frame, looking back at the viewer. Others are seemingly unaware they are being watched, captured unawares. In one a woman sits at a dressing table. We look at her back, with her face reflected in the mirror. We watch her, but is she watching us in the reflection of the mirror? Are we, the viewer, being surveilled as we intrude into her private space? A photograph captures two lovers kissing as a bus with the word ‘sightseeing’ goes past. The word reminds us of our voyeurism – watching the kiss from a distance, in much the same way one might hop on a tour bus to see key landmarks.

Share with us your thoughts, comments and own portraits via email or social media

jcr.artfund@pmb.ox.ac.uk | @pembrokejcrart | #whatyoulookin'at?

Until advancements in photography made getting your portrait taken a relatively inexpensive thing to do, a painted, drawn or sculpted portrait was a significant investment. And sitters wanted value for money – portrayed at their best, showing off their wealth, elegance, beauty and power. Whilst the elaborate sets, props and costumes may have disappeared, we still look to portray ourselves as we wish to be seen, rather than as we are. Think of wedding and graduation photos; think of Instagram and the use of filters. We are not immune to the desire to be seen in an aspirational light.

Our collection holds a handful of portraits of named or identified figures. Some are stylised; some seem more realistic, documentary; whilst others reflect the relationship between sitter and artist. Click on each of the images below to learn more.

Part I. The Great and The Good

Part II. Capturing the Spirit

In 1965 Pembroke student, Andrew Lawson became President of the Oxford University Art Society, and alongside other great speakers the now renowned artist David Hockney (b.1937) agreed to come to Oxford on the 19th May 1965. Lawson recollects,

"I met him at the station. Stepping off the train was an apparition with silky blond hair and dressed in pink from head to foot. He was accompanied by his immensely tall friend, the painter Patrick Procktor. It was a beautiful afternoon and we took them punting on the river. They loved it, especially the vision of athletic and languorous youth. Later we came back to my room at Pembroke, at the top of Staircase 14, overlooking Pembroke Street. With a cheek that surprises me to this day, I dished out paper pads, and the whole group proceeded to draw each other. Hockney made a portrait of Procktor. Procktor’s own drawing emphasised Hockney’s owl-like round spectacles, and included undergraduate Tony Coombs, leaning against the wall, and myself snapping photographs, as well as a hint of the ancient beams of that lovely medieval room."

We are grateful to Andrew Lawson for donating not only the portrait sketches Hockney and Procktor made that day, but also his photographs which captured them in action. And so here we have a double form of portraiture: the artist drawing and the photographer photographing, capturing both at work in portraiture. Portraiture doesn't have to be something which is posed nor poised. The photographs which Lawson took capture not only the artists punting on the river, but also them at work sketching each other - a double record of portraits.

Part III. Portraits in Duet

The portrait is not a singular activity. Firstly, you have the relationship between sitter and painter, and then secondly you can also have the relationship between sitters - sometimes portrayed within the same artistic frame; sometimes linked indirectly through serialisation or separated physically as diptychs or triptychs. When portrayed outside the same pictorial plane the relationship between the sitters becomes reliant on the display of the artworks. Those portraits where two or more figures are portrayed within a single artwork, usually, although not always, reveal the relationship between sitters. This may be a familiar, hierarchical, emotional, cultural or geographical connection. It may be conveyed through the sitters’ poses or emotive expressions; through placement, colouring and technique; through the titling of the work; or merely through the fact that two figures are viewed together.

Part IV. The Voyeur

A debate has ranged in art for a long as artists have captured people in images, centring around questions of looking, being looked at, perception and voyeurism. Essentially questioning ‘What are we looking at?’. Portraiture and figurative work by its very nature necessitates a form of voyeurism – the artist looks the sitter to capture their likeness, and in turn the sitter has the opportunity to watch the artist. There is a sense of exchange between the two: looking and being looked at.

But what’s the dynamic when the subject of the artwork is captured seemingly unawares – in snap shot moment, asleep or looking away? Is the artist invading their private space? Is the artist exploiting the subjects and the situation?

Add in the viewer and this complicates matters. The viewer is a secondary viewer – the sitter, whilst most likely knowing that others will see the resulting artwork, has little agency over who sees it and in what context.

Part V. The Self

Portraiture has long been tied to identity, whether genuine, perceived or portrayed. The sitter, the artist or potentially the sitter and the artists in cahoots contrive what the viewer sees in the resulting artwork. The pose, the gesture, the props, the wardrobe, the makeup, the setting all contribute to a narrative about the subject. But when this is stripped back the viewer is confronted with a portrayal of self which can be ambiguous. The artworks in this section explore how the portrait has been used to portray an individual up close, focusing on the face and head, depicting it without visual context.

All images are courtesy of the artists, their estates, their galleries and the Pembroke College JCR Art Collection.